Our duty is plain. We must search and try our ways, and turn again to the Lord. The loss of his favor will explain everything that has happened. And the grand aim should be to learn how we have lost his favor, and by what means we can regain it. This is too large a theme to be discussed within the compass of a few pages. But there is one feature of our government too closely connected with this question and too conspicuous to be passed by in silence. I refer, as you will readily suppose — for the topic is a familiar one— to the absence of any adequate recognition of the sovereignty of God, and the religion of which he is the author and object, in our Constitution, and in the practical administration of our political system. It may be conceded that the spirit of Christianity is to a certain extent incorporated into our Constitutions. The legal recognition of the Sabbath, the oath on the Holy Evangelists, and the appointment of chaplains, are, so far, an acknowledgment of the Christian religion. But our national charter pays no homage to the Deity. His name does not once occur in the Constitution of the United States. And, as if to confound the charity which would refer this omission to some accidental agency, the same atheism is repeated and perpetuated in another form no less excusable. . . . . The coinage of the United States is without a God. . . . . Is it too much to hope that this opprobrium may be wiped away? If we have never been taught the lesson before, we are admonished of it now, that the ‘Lord reigneth.’ Has not the time come to make our formal national confession of this fundamental truth — to impress it upon our coinage; to insert it (peradventure it may not be too late,) as the keystone of our riven and tottering Constitution? If the country is not ready for these two simple but significant steps in the direction of Christianity, we have been chastened to very little purpose (The Sovereignty of God, the Sure and Only Stay of the Christian Patriot in Our National Troubles: A Sermon (1862), pp. 20-23).

The Constitution Should Contain a Recognition of the Sovereignty of God Over the Nation.

In the consideration of this topic three things will be assumed, as their establishment (in substance) belongs to another tract of this series, viz. -- (1) That every nation is an organism, a moral person, of which Jehovah is Creator and Sovereign; -- (2) That God, as Sovereign, gives a Nation its prosperity and its adversity, and that He gives these for purposes of reward, of chastisement, and of special training; -- (3) That it is the duty of every nation -- especially of every Nation blessed as we have been -- to recognize, as an organism, His Sovereignty (The Religious Defect of the Constitution of the United States (1868), pp. 1-2).

There is one strictly national, that commenced in the adoption of the Federal Constitution, which is, the want of an acknowledgment in it of a Supreme Being and of a Divine revelation. That all-important engine of our national prosperity is, in form at least, entirely atheistical. Undoubtedly it was a great sin to have forgotten God in such an important national instrument, and not to have acknowledged Him in that which forms the very nerves and sinews of the political body. He had led us through all the perils of the Revolutionary struggle, and had established us in peaceful and plentiful security, and then to have been forgotten in the period of prosperity, certainly demanded His rebuke. Therefore hath the voice of His Providence proclaimed and even still it sounds in our ears: “I did know thee in the wilderness, in the land of great drought. According to their pasture, so were they filled; they were filled, and their heart was exalted; therefore have they forgotten me. Therefore will I be unto them as a lion; as a leopard by the way will I observe them” (Judgment and Mercy: A Sermon, Delivered...On the Day of "Humiliation, Thanksgiving, and Prayer" (1820)).

George Duffield V (not an NRA officer):

“Ye have robbed me, even this whole nation,” and as a nation He will hold us responsible for this robbery of his service and honor, just as much as he did Israel, and Babylon, and Persia, and Greece and Rome. To deny that God is ‘“THE GOVERNOR OF THE NATIONS,” (Ps. xxii. 28,) is to deny HIS DIVINE PROVIDENCE, acknowledged in the Declaration of Independence, and to deny the providence of God is to deny his ATTRIBUTES. * * * It is that old story of Israel and human nature over again: “Jeshurun waxed fat and kicked.” Temporal prosperity was too much for him. “Then he forsook the God which made him, and lightly esteemed the Rock of his salvation.’” (Deut. xxxii. 15.”)

* "That no notice whatever should be taken of that God who planteth a nation, and plucketh it up at his pleasure, is an omission which no pretext whatever can palliate. Had such a momentous business been transacted by Mohammedans, they would have begun, "In the name of God." Even the savages, whom we despise, setting a better example, would have paid some homage to the Great Spirit. But from the Constitution of the United States, it is impossible to ascertain what God we worship; or whether we own a God at all. * * Should the citizens of America be as irreligious as her Constitution, we will have reason to tremble, lest the Governor of the Universe, who will not be treated with indignity by a people, any more than by individuals, overturn, from its foundation, the fabric we have been rearing, and crush us to atoms in the wreck." —Works of J. M. Mason, D. D., Vol. i., p. 50.

“Was this omission intentional, as in the original draft of the Declaration of Independence? or was it a moral oversight, even greater than the tremendous political oversight in the original Articles of Confederation?” "Is it not strange that it appears not to have been perceived by any one at the time that the whole of this controversy arose out of a departure from the principles of the Declaration of Independence, and the substitution of State sovereignty, instead of the constituent sovereignty of the people, as the foundation of the Revolution and the Union?" — ''Jubilee of the Constitution," by John Quincy Adams, April 30th, 1839, pp. 30-36 (The God of Our Fathers: An Historical Sermon (1861), pp. 13-15).

We have formed an association to effect an amendment to the Constitution of the United States. Our proposed amendment does not touch to change — much less to abrogate — one of the truths, the principles or the features of that great instrument. Nor does it imply that we are wanting in appreciation of it; that we are dissatisfied or are restless under its working hitherto. Whoever likes the Constitution will find that we like it, and the institutions that have grown up under it, in the same measure and probably for the same good reasons. He will find us joined with him in the loyal support of all the good that is in it, its implied assertion of the rights of man and its wise provision for the growth of the nation. For such political wisdom given to our fathers we devoutly thank God; and it is our conviction and our boast that this Constitution is the best national charter recorded on the pages of history. But our fathers were not infallible, and the Constitution which they made for us was not perfect. Our nation's growth and experience have suggested several important amendments which have been already adopted ; and, as it seems to us, the time has come to discuss the adoption of another. There are certain evils and cer tain signs of coming evil which give us anxiety. These evils and evil omens we trace back to an omission in the Constitution, and it is evident that if this omission be supplied the evils will be averted. And this is what we propose to do. Our amendment, like all the others, is suggested by our experience, and, however it may seem to be late in the day, can never be out of date. There is no mention of God in the Constitution, no word which recognizes His sovereignty over human affairs or His interest in them. One of the great — one of the chief characteristics of our people at the time they entered into national com pact is thus ignored. The underlying faith of our forefathers, a faith which must have given life and shape to their politics and their institutions, is thus not alluded to. I repeat, this is the omission which now engages our attention and which we wish to supply. We feel that such an omission does injustice to the people, who, because of it, are but partially described and but partially represented in their Constitution. It would seem as if they had not understood how great and how grave was the work of nation-making in which they were engaged, and that they gave to.it only such earnestness as showed their desire for safety peace and wealth — mere material interests — though our forefathers, as we know, were a serious, thoughtful people, accustomed to do everything of a public nature in the name and the fear of God ; and though they settled the land and made their laws from the beginning as much for religious faith as for civil freedom, or rather, for the freedom of religious faith (Address of Dr. Edwards to the National Convention to Secure the Religious Amendment of the Constitution of the United States (1872)).

It is often claimed that the omission of all reference to God and His authority was simply an oversight; that His name was dropped from the oath by a mere inadvertence, and that the "no religious test" clause meant only no sectarian test; that some of the colonies had adopted sectarian tests, and that this was intended to forbid such tests under the Constitution. There are two things to be said in reply to this claim: First, that such deep forgetfulness and such astounding inadvertence in so grave a matter and in such circumstances, is wholly incredible and would scarcely lessen the nation's guilt if it were true. "For the wicked shall be turned into hell and all the nations that forget God." And, second, there are historical facts connected with the framing, adoption, and first administration of the Constitution, which put beyond all question that our Constitution and government has this Godless, Christless character by the design and purpose of its founders (Lectures in Pastoral Theology, Vol. 3 (The Covenanter Vision) (1917), p. 293).

It is time that, without any narrowness or bigotry, Christians were united in the affirmation that this is and shall be a Christian land, and that the acknowledgment of this truth shall be put beyond all peradventure by being formally in the National Constitution (Letter to David McAllister, December 11, 1873).

This Church [Reformed Presbyterian (Covenanter) Church of North America] is the special leader in the National Reform Movement. This is in the line of its testimony from the earliest days of Scotch Presbyterianism down to the present time. The thing which is peculiar to the Reformed Presbyterian Church (Old Side) and which distinguishes it from all others, is the refusal of its people to vote, hold office, or do any other act definitely incorporating themselves with the government until the nation shall specifically recognize Jesus Christ as the source of its civil authority, and God's law as the rule of national conduct in legislation and in the administration of its affairs, both international and domestic. While the Covenanter Church is alone in maintaining the consistency of its political dissent by refusing to vote, large numbers of Christian American citizens in other communions look upon it as a radical, if not fatal defect of the Constitution that it contains no recognition of God as supreme, or of the nation as a moral person bound by the moral law. The Constitution acknowledges no benefit to be derived from the Bible, the Sabbath, Christian morality, or Christian conduct in officials, and gives no legal basis for any Christian feature of the government.

...Reformed Presbyterians feel specially called upon to aid the success of this association at any cost or personal sacrifice. They believe that when the proposed amendments to the Constitution shall have been incorporated into that document, and not until then, shall this be a truly Christian government.

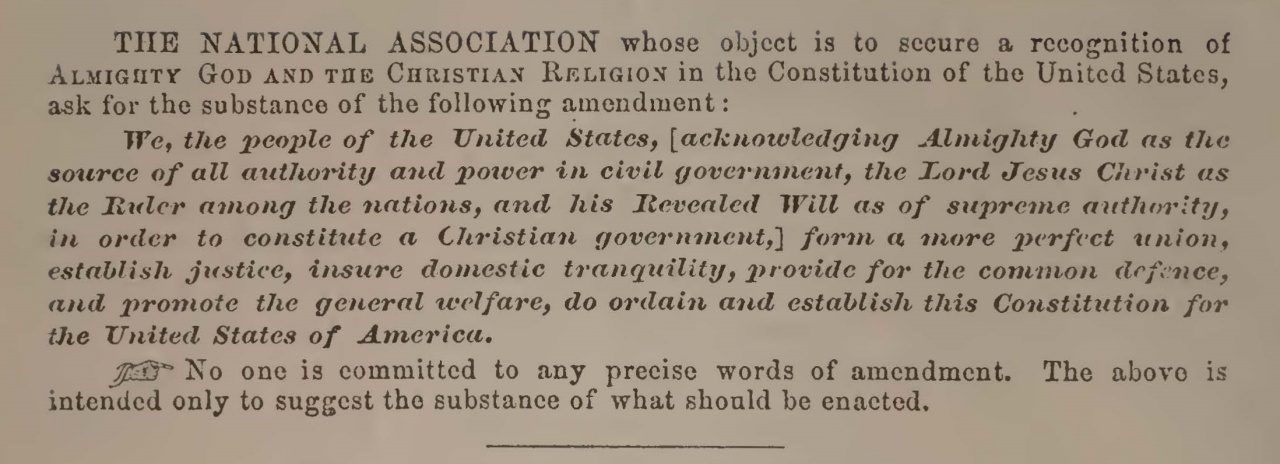

...That Movement seeks to add to the Preamble of the Constitution of the United States, as the source of its civil authority some acknowledgment of God and the Nation's accountability to him. At present the Preamble of the Constitution simply says 'We, the people of the United States,' as if the people were independent of the Almighty. The National Reform Association seeks to have that Preamble amended by inserting after the words just quoted, 'recognizing the dominion of Jesus Christ over the nations, and this nation's subjection to the Divine law (Presbyterians: A Popular Narrative of Their Origin, Progress, Doctrines, and Achievements (1892), pp. 420-421).

Christ’s Mediatorial authority embraces the universe.—Matthew 28:18; Philippians 2:9–11; Ephesians 1:17–23. It presents two great aspects. 1st. In its general administration as embracing the universe as a whole. 2nd. In its special administration as embracing the church…

The truth as held by all branches of the historical church is, that while Christ has been virtually Mediatorial King as well as Prophet and Priest from the fall of Adam, yet his public and formal assumption of his throne and inauguration of his spiritual kingdom dates from his ascension and session at the right hand of his Father….

The state is a divine institution, and the officers thereof are God’s ministers, Romans 13:1–4, Christ the Mediator is, as a revealed fact, “Ruler among the Nations,” King of kings, and Lord of lords, Revelation 19:16; Matthew 28:18; Philippians 2:9–11; Ephesians 1:17–23, and the Sacred Scriptures are an infallible rule of faith and practice to all men under all conditions…

It follows therefore— 1st. That every nation should explicitly acknowledge the Christ of God to be the Supreme Governor, and his revealed will the supreme fundamental law of the land, to the general principles of which all special legislation should be conformed. 2nd. That all civil officers should make the glory of God their end, and his revealed will their guide. 3rd. That, while no distinction should be made between the various Christian denominations, and perfect liberty of conscience and worship be allowed to all men, nevertheless the Christian magistrate should seek to promote piety as well as civil order (“Confession of Faith,” ch. 23, § 2). This they are to do, not by assuming ecclesiastical functions, nor by attempting to patronize or control the church, but by their personal example, by giving impartial protection to church property and facility to church work, by the enactment and enforcement of laws conceived in the true spirit of the Gospel, and especially in maintaining inviolate the Christian Sabbath, and Christian marriage, and in providing for Christian instruction in the public schools (Outlines of Theology, pp. 428-429, 434).

The point we want recognized in the Constitution is not a dogma of the churches, nor a theory of the schools, but a simple fact, everywhere operating, and universally recognized by believers. Jesus Christ is, as a fact, “Ruler among the nations,” (I.) providentially guiding their affairs, and determining their destinies; (2.) morally, by the revelation of truth and duty, the exhibition of motives, and stimulus and discipline of providentially arranged circumstances. If this be a matter of fact generally believed, should not a great self-governing community like this nation, conscious of its acts and of their character, make a distinct profession of its allegiance?

The practical recognition of this fact is no new thing in American history. It has formed a prominent characteristic of our successive governments, colonial, state, and national, from the beginning. We propose the adoption of no new principles, and no radical change of customs. We propose only to recognize, as a fundamental principle in the National written Constitution, that which has been a universally recognized principle of national life from the first. We aim not at change, but at conservation. We want to preserve through all coming time, and consistently carry out in all departments of law, the hitherto universally admitted fact, that Christianity is an element in the common law of the land (Address Concerning a Religious Amendment to the U.S. Constitution (1874)).

The grand defect in the bond of our national union is the absence of the recognition of God as the Governor of this world. We have omitted — may it not be said refused? — to own him whose head wears many crowns, as having any right of dominion over us. The constitution of these United States contains no express recognition of the being of a God: much less an acknowledgment, that The Word of God, sways the sceptre of universal dominion. This is our grand national sin of omission. This gives the infidel occasion to glory, and has no small influence in fostering infidelity in affairs of state and among political men. That the nation will be blessed with peace and prosperity continuously, until this defect be remedied, no Christian philosopher expects. For this national insult, the Governor of the universe will lift again and again his rod of iron over our heads, until we be affrighted and give this glory to his name (The Little Stone and the Great Image; or, Lectures on the Prophecies Symbolized in Nebuchadnezzar's Vision of the Golden Headed Monster (1844), pp. 280-281).

We have never believed it perfect. Doubtless some improvements are possible; but it makes abundant provision for them, without utter demolition. The principal defect apparent to our vision meets us at the vestibule. The portico lacks one gem to perfect its lustre. There is union and justice, common defence and general welfare, blessing and liberty, but we cast our eyes about in vain for that which alone can give stability and beauty to the whole. The Koh-i-noor, whose radiant glories crown the grandeur of the beautiful temple, the Shekinah, is absent. The grand bond of our national Union does not distinctly acknowledge the being of a God. For more than forty years, a Fourth of July has seldom passed, on which I have not preached and warned my countrymen of this defect, and told them if it be not supplied, God would pull down their temple and bury a nation in its ruins. This warning has been sounded forth from thousands of pulpits in the land, and would have been much more extensively trumpeted but for the paralyzing influence of the fallacy couched in the demagogue's double entendre. ‘Religion has nothing to do with politics’ (Political Fallacies (1863), pp. 305, 306).

Nations have no difficulty in recognizing and acting on the principle of national, responsibility in their dealings with each other. In our recent troubles with Spain on account of the capture of the Virginius and the barbarous deeds that followed, we did not go to the individuals who perpetrated the outrage; we did not go to Cuba with our demand of reparation; we took our case directly to those who represented the supreme authority of Spain. From the nation we demanded reparation, and from it we received it. On the same principle God deals with all nations. They may refuse to acknowledge his authority; they may seek to throw off all responsibility to him; but it is in his prerogative and power to hold them to it, whether they acknowledge it or not. He claims, not only under his general ordinance, but in specific terms, to be the “Governor among the nations;” and in his Providence, as in his word, has shown that he does “judge among the nations,” and that “blessed is the nation whose God is the Lord.” The sacred history abounds with records of this, not only in respect to the chosen people, but the nations around them whose history is interwoven with theirs. And in records outside of the sacred history, we have the evidences, in all the ages, of his judgment and power, approving or condemning, blessing or punishing, the nations according to their character and acts. The history of our own nation is a sufficient illustration of this; as, also, of the fact that no existing nation of all the world has been brought under greater obligations to acknowledge and honor him (Moral Responsibility of Nations (1874)).

The amendment proposed is such an addition, in substance, to the Preamble of the United States Constitution, as will suitably express our national acknowledgment of Almighty God as the author of the nation's existence and the source of its authority; of Jesus Christ as its ruler; and of the Bible as the fountain of its laws and the supreme rule of its conduct.

This is the great purpose of the National Association, based on the fundamental truth that a nation, as such, stands in clear and definite relations to God and his moral laws, and that in the Constitution, as well as the administration of its government, it is under obligations to acknowledge these relations (The Aims and Methods of the Movement to Secure the Religious Amendment of the Constitution of the United States (1872)).

The doctrine here advocated is, that as the different branches of our national government, the executive, legislative, and judicial, are co-ordinate, each supreme within its own sphere, and independent of the others, but all alike responsible directly to the people, so the church and state are co-ordinate institutions, totally independent of each other, each, in its own sphere, supreme with respect to the other, but both alike of Divine appointment, having one and the same head and fountain of all their powers, which is God. Whence both alike are bound to acknowledge, worship, and obey him. It is as great a solecism for the state to neglect this, as it would be for the church. Many seem to think that the complete separation of church and state, implies that the state, as such, has no duties to God, and no religious character. As logically it could be inferred from the family’s independence of the church, that that family has no religious character, and no duties to God. The family, the church, and the state, these are all co-ordinate institutions, severally independent of each other, yet all alike having one and the same Head, which they are equally bound in solemn form to acknowledge, worship, and obey. When the state, for any reason, declines to do this, it falls into a gross anomaly, and exemplifies that which is described in the second Psalm: Why do the nations rage, and the people imagine a vain thing? The kings of the earth set themselves, and the rulers take counsel together, against Jehovah, and against his Anointed, saying, Let us break their bands asunder, and cast away their cords from us. He that sitteth in the heavens shall laugh; Jehovah shall have them in derision (A Nation’s Right to Worship God (1859), pp. 36-37).

Nor is slavery by any means the only sin with which, as a nation, we are chargeable. Our constitution of government, and its administration, are, to all intents and purposes, atheistic, ignoring the existence of God and every institution that he has established among men. This constitution was formed at a period when this country and Europe were both overrun by the principles of French infidelity, by men who were notoriously sceptical, and by whom all recognition of God was purposely excluded from this “remarkable document.” This no one can deny who has any acquaintance with the history of this period (God's Judgments, and Thanksgiving Sermons: A Discourse (1858), p. 12).

The first which I name, Religion, is first also in point of importance and necessity. This is a prime support of national greatness and perpetuity. No government, much less one that is wholly dependent upon the morals of the citizens, will long exist without it. By religion in this connection, I do not mean merely the religion of the individuals composing the State, but national religion acknowledged in the Constitution, embodied in the laws, and entering as an element into all those institutions which are the outgrowth and the exponents of the national life….We refuse, then, the profane maxims current in the mouths of political speculatists: "Religion has nothing to do with politics," "The State has no God," "Law knows no Bible."…We do not affirm that as a nation we are wholly destitute of the Christian element. There is much in our country which is the direct result of its influence. There are certainly here a large number devotedly attached to Christian principles. Our great benevolent and educational institutions are largely moulded and controlled by Christianity. Its powerful and permeating influence is everywhere felt. Nevertheless, as a government, we are not merely profoundly laic, as Guizot would say, but absolutely infidel and atheistic. Our Government is no more Christian than it is Jewish or Mohammedan. There is no recognition of God in its Constitution, no allusion to his name, authority, or law, not the most remote allusion to that great fundamental truth which, as the General Assembly in its late deliverance upon this subject truly declares, must underlie all our claims to be considered a Christian nation; viz., that there is one mediator between God and man (The Three Pillars of a Republic (1862) in Life and Work of J.R.W. Sloane, D.D. (1888), pp. 235, 238-240).

We respectfully submit to your consideration, whether these amendments are not simply an appropriate recognition of the relations which all just human authority sustains to the Supreme Ruler of the Universe. Is not anything less than this wholly inconsistent with those relations? We propose the recognition of God, not only be cause He is the Supreme Ruler of all men and all organizations, but because it is He who has given the institution of civil government to man, and the just authority of the magistrate is derived from Him. "There is no power but of God. The powers that be are ordained of God." It is surely fitting that a constitution framed by a Christian people should recognize a higher source of civil authority than the mere will or con sent of the. citizen. And in presenting civil government thus, as a divine institution, we enforce, by the highest possible sanctions, its claims upon the respect and obedience of the citizen. The true strength of a government lies in the conscientious regard felt for it as the ordinance of God. Thus only is the magistrate clothed with his true authority, and the majesty of the law suitably preserved. "The sanctions of religion," says De Witt Clinton, "compose the foundations of good government."

Government is instituted for man as an intellectual, social, and moral and religious being. It corresponds to his whole nature. It is intended (o protect and advance the higher as well as the lower interests of humanity. It acts for its legitimate purposes when it watches over domestic life, and asserts and enforces the sanctity of the marriage bond ; when it watches over intellect and education, and furnishes means for developing all the faculties of the mind; when it frowns on profaneness, lewdness, the desecration of the Sabbath, and other crimes which injure society chiefly by weakening moral and religious sentiment, and degrading the character of a people. Acting for such purposes, government should be established on moral principles. Moral principles of conduct are determined by moral relations. The relations of a nation to God and his moral laws are clear and definite: 1. A nation is the creature of God. 2. It is clothed with authority derived from God. 3. It owes allegiance to Jesus Christ, the appointed Ruler of nations. 4. It is subject to the authority of the Bible, the special revelation of moral law. In constituting and administering its government, then, a nation is under obligations to acknowledge God as the author of its existence and the source of its authority, Jesus Christ as its ruler, and the Bible as the fountain of its laws and the supreme rule of its conduct.

Up to the time of the adoption of the National Constitution, acknowledgments of this kind were made by all the States. They are yet made by many of the States. And in the actual administration of the national government the principle is admitted. But the fundamental law of the nation, the Constitution of the United States, on which our government rests and according to which it is to be administered, fails to make, fully and explicitly, any such acknowledgment. This failure has fostered among us mischievous ideas like the following: The nation, as such, has no relations to God ; its authority has no higher source than the will of the people; government is instituted only for the lower wants of man ; the State goes beyond its sphere when it educates religiously, or legislates against profanity or Sabbath desecration.

The National Association, which has been formed for the purpose of securing such an amendment to the Constitution as will remedy this great defect, and indicate that this is a Christian nation, and place all Christian laws, institutions, and usages in our government on an undeniable legal basis in the fundamental law of the nation, invites all American citizens who favor such an amendment, without distinction of party or creed, to meet in Thorns' Hall, Cincinnati, on Wednesday, January 31, 1872, at 2 o'clock, P. M. All such citizens, to whose notice this call may be brought, are requested to hold meetings and appoint delegates to the Convention (Call For a National Convention (1872)).

Persuaded that God is the source of all legitimate power; that he has instituted civil government for His own glory and the good of man; that he has appointed His Son, the Mediator, to headship over the nations; and that the Bible is the supreme law and rule in national as in all other things, we will maintain the responsibility of nations to God, the rightful dominion of Jesus Christ over the commonwealth, and the obligation of nations to legislate in conformity with the written Word. We take ourselves sacredly bound to regulate all our civil relations, attachments, professions and deportment, by our allegiance and loyalty to the Lord, our King, Lawgiver and Judge; and by this, our oath, we are pledged to promote the interests of public order and justice, to support cheerfully whatever is for the good of the commonwealth in which we dwell, and to pursue this object in all things not forbidden by the law of God, or inconsistent with public dissent from an unscriptural and immoral civil power. We will pray and labor for the peace and welfare of our country, and for its reformation by a constitutional recognition of God as the source of all power, of Jesus Christ as the Ruler of Nations, of the Holy Scriptures as the supreme rule, and of the true Christian religion;. and we will continue to refuse to incorporate by any act, with the political body, until this blessed reformation has been secured (The Covenant of 1871)