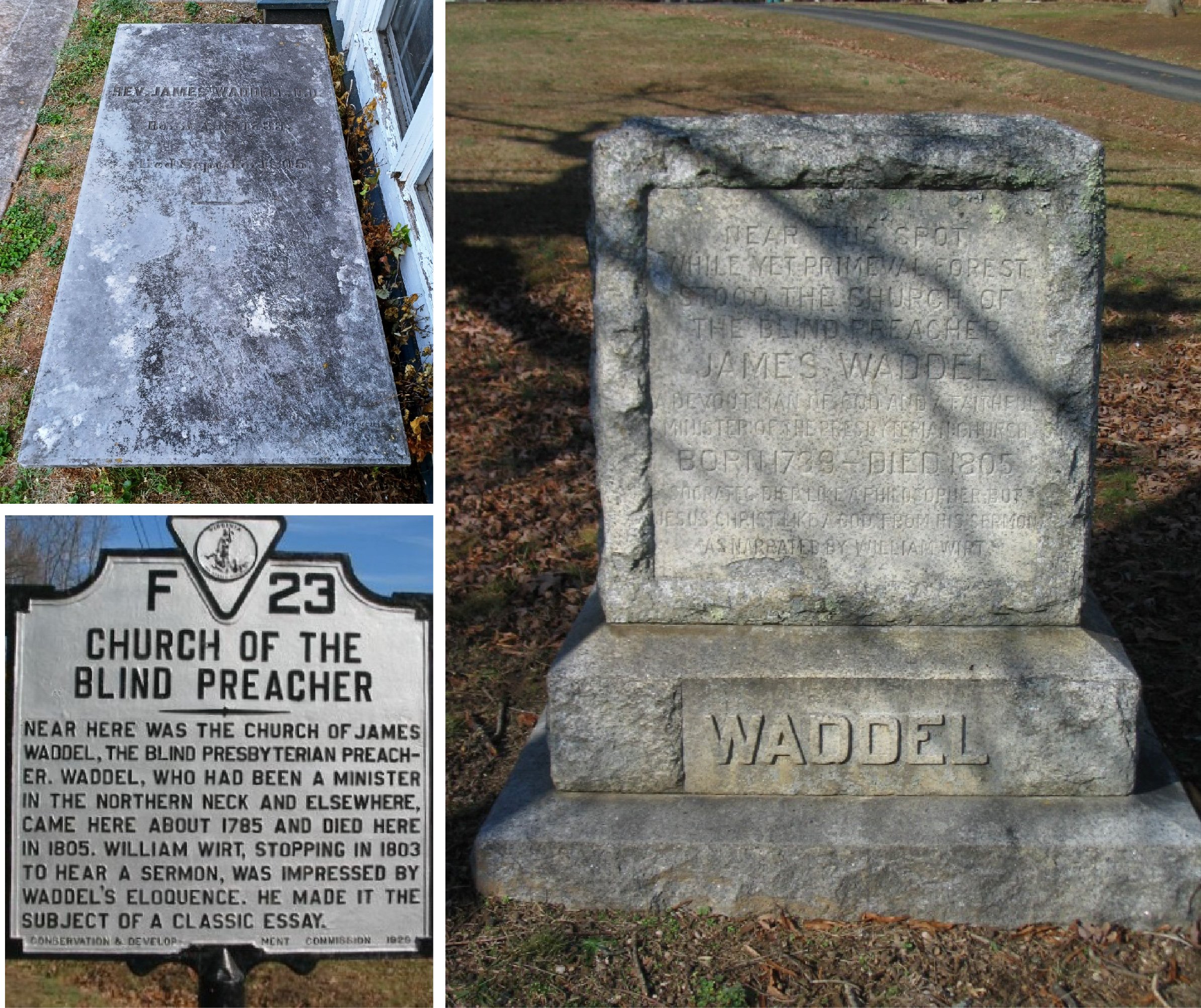

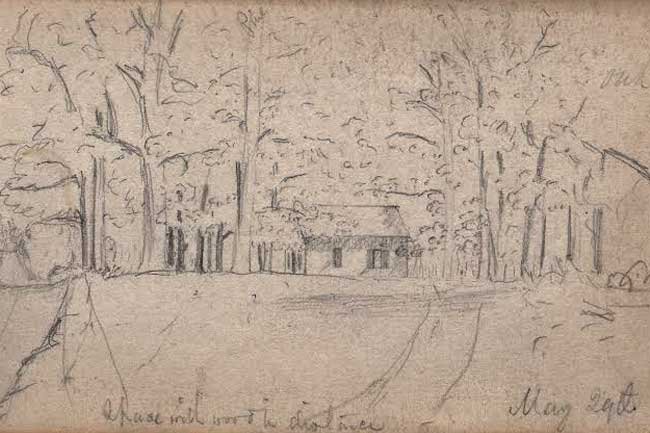

It was one Sunday, as I travelled through the county of Orange, that my eye was caught by a cluster of horses tied near a ruinous, old, wooden house, in the forest, not far from the roadside. Having frequently seen such objects before, in travelling through these states, I had no difficulty in understanding that this was a place of religious worship.

Devotion alone should have stopped me, to join in the duties of the congregation; but I must confess, that curiosity, to hear the preacher of such a wilderness, was not the least of my motives. On entering, I was struck with his preternatural appearance, he was a tall and very spare old man; his head, which was covered with a white linen cap, his shrivelled hands, and his voice, were all shaking under the influence of a palsy; and a few moments ascertained to me that he was perfectly blind.

The first emotions which touched my breast, were those of mingled pity and veneration. But ah! sacred God! how soon were all my feelings changed! The lips of Plato were never more worthy of a prognostic swarm of bees, than were the lips of this holy man! It was a day of the administration of the sacrament; and his subject, of course, was the passion of our Saviour. I had heard the subject handled a thousand times: I had thought it exhausted long ago. Little did I suppose, that in the wild woods of America, I was to meet with a man whose eloquence would give to this topic a new and more sublime pathos, than I had ever before witnessed.

As he descended from the pulpit, to distribute the mystic symbols, there was a peculiar, a more than human solemnity in his air and manner which made my blood run cold, and my whole frame shiver.

He then drew a picture of the sufferings of our Saviour; his trial before Pilate; his ascent up Calvary; his crucifixion, and his death. I knew the whole history; but never, until then, had I heard the circumstances so selected, so arranged, so coloured! It was all new: and I seemed to have heard it for the first time in my life. His enunciation was so deliberate, that his voice trembled on every syllable; and every heart in the assembly trembled in unison. His peculiar phrases had that force of description that the original scene appeared to be, at that moment, acting before our eyes. We saw the very faces of the Jews: the staring, frightful distortions of malice and rage. We saw the buffet; my soul kindled with a flame of indignation; and my hands were involuntarily and convulsively clinched.

But when he came to touch on the patience, the forgiving meekness of our Saviour: when he drew, to the life, his blessed eyes streaming in tears to heaven; his voice breathing to God, a soft and gentle prayer of pardon on his enemies, 'Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do' — the voice of the preacher, which had all along faltered, grew fainter and fainter, until his utterance being entirely obstructed by the force of his feelings, he raised his handkerchief to his eyes, and burst into aloud and irrepressible flood of grief. The effect is inconceivable. The whole house resounded with the mingled groans, and sobs, and shrieks of the congregation.

It was some time before the tumult had subsided, so far as to permit him to proceed. Indeed, judging by the usual, but fallacious standard of my own weakness, I began to be very uneasy for the situation of the preacher. For I could not conceive, how he would be able to let his audience down from the height to which he had wound them, without impairing the solemnity and dignity of his subject, or perhaps shocking them by the abruptness of the fall. But — no; the descent was as beautiful and sublime, as the elevation had been rapid and enthusiastic.

The first sentence, with which he broke the awful silence, was a quotation from Rousseau, 'Socrates died like a philosopher, but Jesus Christ, like a God!' I despair of giving you any idea of the effect produced by this short sentence, unless you could perfectly conceive the whole manner of the man, as well as the peculiar crisis in the discourse. Never before, did I completely understand what Demosthenes meant by laying such stress on delivery. You are to bring before you the venerable figure of the preacher; his blindness, constantly recalling to your recollection old Homer, Ossian and Milton, and associating with his performance, the melancholy grandeur of their geniuses; you are to imagine that you hear his slow, solemn, well-accented enunciation, and his voice of affecting, trembling melody; you are to remember the pitch of passion and enthusiasm to which the congregation were raised; and then, the few minutes of portentous, death-like silence which reigned throughout the house; the preacher removing his white handkerchief from his aged face, (even yet wet from the recent torrent of his tears,) and slowly stretching forth the palsied hand which holds it, begins the sentence, 'Socrates died like a philosopher' — then pausing, raising his other hand, pressing them both clasped together, with warmth and energy to his breast, lifting his 'sightless balls' to heaven, and pouring his whole soul into his tremulous voice — 'but Jesus Christ — like a God!' If he had been indeed and in truth an angel of light, the effect could scarcely have been more divine.

Whatever I had been able to conceive of the sublimity of Massillon, or the force of Bourdaloue, had fallen far short of the power which I felt from the delivery of this simple sentence. The blood, which just before had rushed in a hurricane upon my brain, and, in the violence and agony of my feelings, had held my whole system in suspense, now ran back into my heart, with a sensation which I cannot describe — a kind of shuddering delicious horror! The paroxysm of blended pity and indignation, to which I had been transported, subsided into the deepest self-abasement, humility and adoration. I had just been lacerated and dissolved by sympathy, for our Saviour as a fellow creature; but now, with fear and trembling, I adored him as — 'a God!'

If this description gives you the impression, that this incomparable minister had any thing of shallow, theatrical trick in his manner, it does him great injustice. I have never seen, in any other orator, such a union of simplicity and majesty. He has not a gesture, an attitude or an accent, to which he does not seem forced, by the sentiment which he is expressing. His mind is too serious, too earnest, too solicitous, and, at the same time, too dignified, to stoop to artifice. Although as far removed from ostentation as a man can be, yet it is clear from the train, the style and substance of his thoughts, that he is, not only a very polite scholar, but a man of extensive and profound erudition. I was forcibly struck with a short, yet beautiful character which he drew of our learned and amiable countryman, Sir Robert Boyle: he spoke of him, as if 'his noble mind had, even before death, divested herself of all influence from his frail tabernacle of flesh;' and called him, in his peculiarly emphatic and impressive manner, 'a pure intelligence: the link between men and angels.'

This man has been before my imagination almost ever since. A thousand times, as I rode along, I dropped the reins of my bridle, stretched forth my hand, and tried to imitate his quotation from Rousseau; a thousand times I abandoned the attempt in despair, and felt persuaded that his peculiar manner and power arose from an energy of soul, which nature could give, but which no human being could justly copy. In short, he seems to be altogether a being of a former age, or of a totally different nature from the rest of men. As I recall, at this moment, several of his awfully striking attitudes, the chilling tide, with which my blood begins to pour along my arteries, reminds me of the emotions produced by the first sight of Gray's introductory picture of his bard:

On a rock, whose haughty brow,

Frowns o'er old Conway's foaming flood,

Robed in the sable garb of wo,

With haggard eyes the poet stood;

(Loose his beard and hoary hair

Streamed, like a meteor, to the troubled air:)

And with a poet's hand and prophet's fire.

Struck the deep sorrows of his lyre.

Guess my surprise, when, on my arrival at Richmond, and mentioning the name of this man, I found not one person who had never before heard of James Waddell!! Is it not strange, that such a genius as this, so accomplished a scholar, so divine an orator, should be permitted to languish and die in obscurity, within eighty miles of the metropolis of Virginia?